17 Jun 2016

Posted

in Banking, Economy, Government, Macroeconomics, Manufacturing, Metals & Mining, Uncategorized

The Maastricht Treaty has been slowly asphyxiating any possibility of sustained economic recovery in Britain. It has been partially responsible for the erratic recovery of manufacturing, production and construction industries.

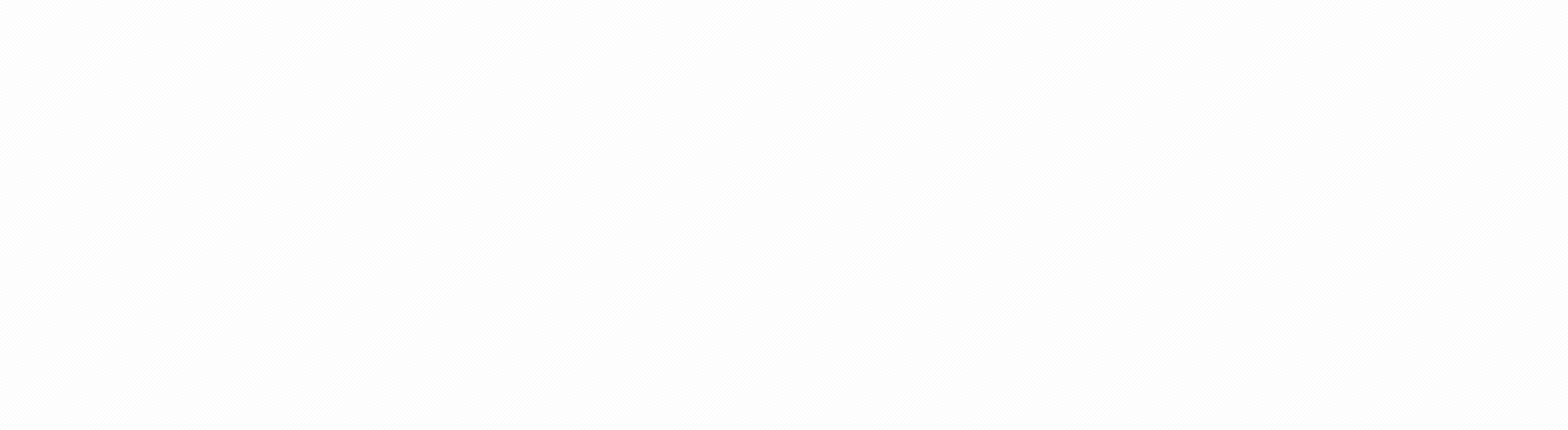

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of Britain peaked back at pre-crisis level in the second quarter of 2013 driven mainly by the growth of the services industry. This industry is 13 per cent larger in value compared to 2009 (figure below). Production, construction and manufacturing industries are on average 7% smaller than their pre-crisis levels.

The majority of UK industries are still underwater due to a lack of private demand coming from UK and the Euro area, which is a major export partner. To make matters worse, government expenditure in the Euro area and in the UK could have filled the demand gap from the private sector. However, it has been held back by European Maastricht treaty. According to the Treaty, budget deficits cannot be higher than 3 per cent of GDP and national debt must be below 60 per cent of GDP.

GDP and main components relative to 2008

The Bank of England under Mervin King and, more recently, under McCarney’s leadership responded to the events in the aftermath of Great Financial crisis. Their goal was to push the GDP number up from a 6% contraction (figure above) maintaining price stability. It was expected that more credit available in the financial sector would support the overall level of activity within the economy including manufacturing, construction and production.

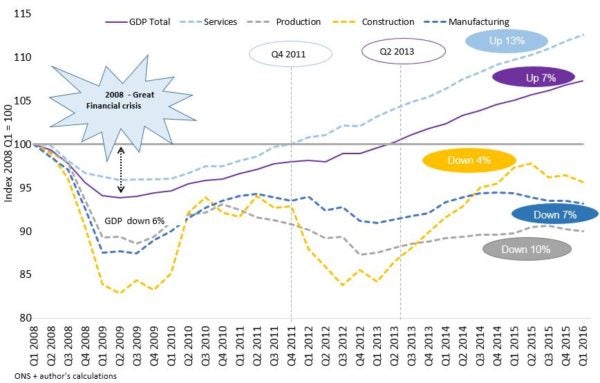

As of April 2016, the Bank of England has purchased £375bn ($594bn) worth of assets from the financial institutions in the UK and, consequently, increased the money holdings of the financial sector by the same magnitude (second figure below).

Bank of England injection of cash into the economy

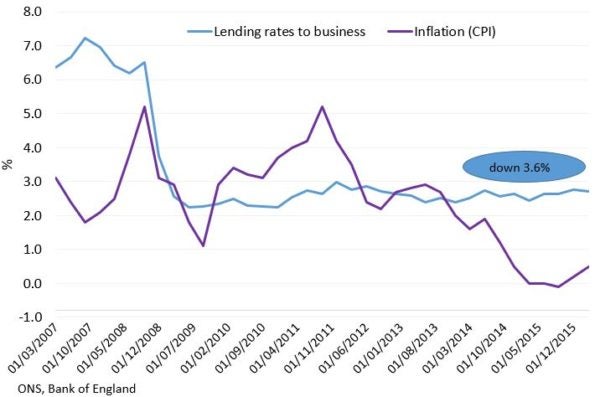

As predicted by the QE program, the inflow of money within the financial sector lowered the borrowing costs to business (third figure below – lending rates to business) but it is yet to be matched by more lending. Borrowing costs went down by 3.6% (figure above – lending rates to business) but manufacturers have borrowed 21% less in 2016 compared to 2011 (second figure). It is fair to say that industries reduced their plans to invest in the British economy due to a lack of consumer and government spending and fear of an even worse prolonged slump.

Lending rates and inflation in Britain

All the industries, apart from services, embarked on an erratic recovery after the third quarter of 2009 (first figure). It is an indication that the QE has been having an effect on the economy but the full recovery remains largely subdued to this date.

Britain is struggling to recover from the recession even if newspapers’ headlines are optimistic about the British economy. Industries drastically reduced their levels of borrowing due to a sustained lack of internal and external demand for its products.

The rigid structure of the Maastricht Treaty, as pointed above, has played part in dragging the entire EU block into eight years of economic limbo. It fails to allow the public sector to intervene, via expenditure, in their economies to drag them out of the difficult times in the absence of private demand.

It is clear that the Maastricht Treaty needs to be revised to account for periods of economic crisis. Any further integration between EU economies is unthinkable.